A surprise ray of hope on a mountain, and in last week's news

I’m standing in the middle of a cobblestone plaza in a mountain village at the center of an island in the Atlantic Ocean. A speck within a speck within a speck on a planet that looks, from here, especially blue and green.

A 270-degree view of a valley unfolds around me. A winding road snakes from rocky outcroppings in the distance, between pine and palm trees, through fields of grazing sheep, and up to this overlook. The scene is quiet, save for the whisper of the breeze and the intermittent distant whine of a car’s engine climbing the valley walls. Everything glows in pre-dusk sunshine.

There’s something otherworldly about this shimmering landscape. It’s easy to see why the U.N. designated nearly half of this island a World Biosphere Reserve in 2005.

But my attention isn’t on the view. I’m standing, mouth open, in front of a plaque at the base of the monument in the center of the plaza.

It’s about a half hour before sunset in Artenara on the island of Gran Canaria. January 2025, just days before the U.S. presidential inauguration. Danny and I are on vacation before we move to Germany for five months. We’re tired from a day of hiking (both) through the sand dunes on the island’s southern coast with an explosive bloody nose (just me), and we’ve stopped here on the way back to our lodging to see if we can find some dinner. We’ve struck out on that count. But we’ve also been struck by the views here, enough to forget our hunger and explore.

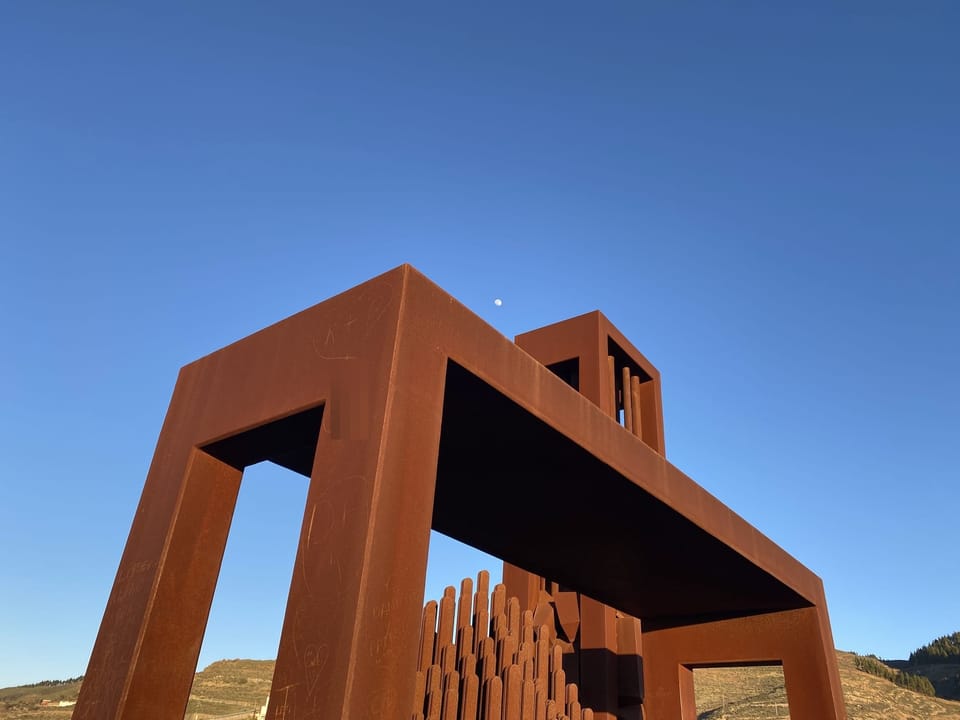

We’d noticed the tall, boxy monument from the town center below and picked our way up the road to investigate. Two rusted iron sculptures glowed red-gold in the long rays of the sun settling behind the opposite rim of the Tejeda caldera. We’d poked around for a bit, taking pictures, until I noticed the plaque that made my heart skip a beat:

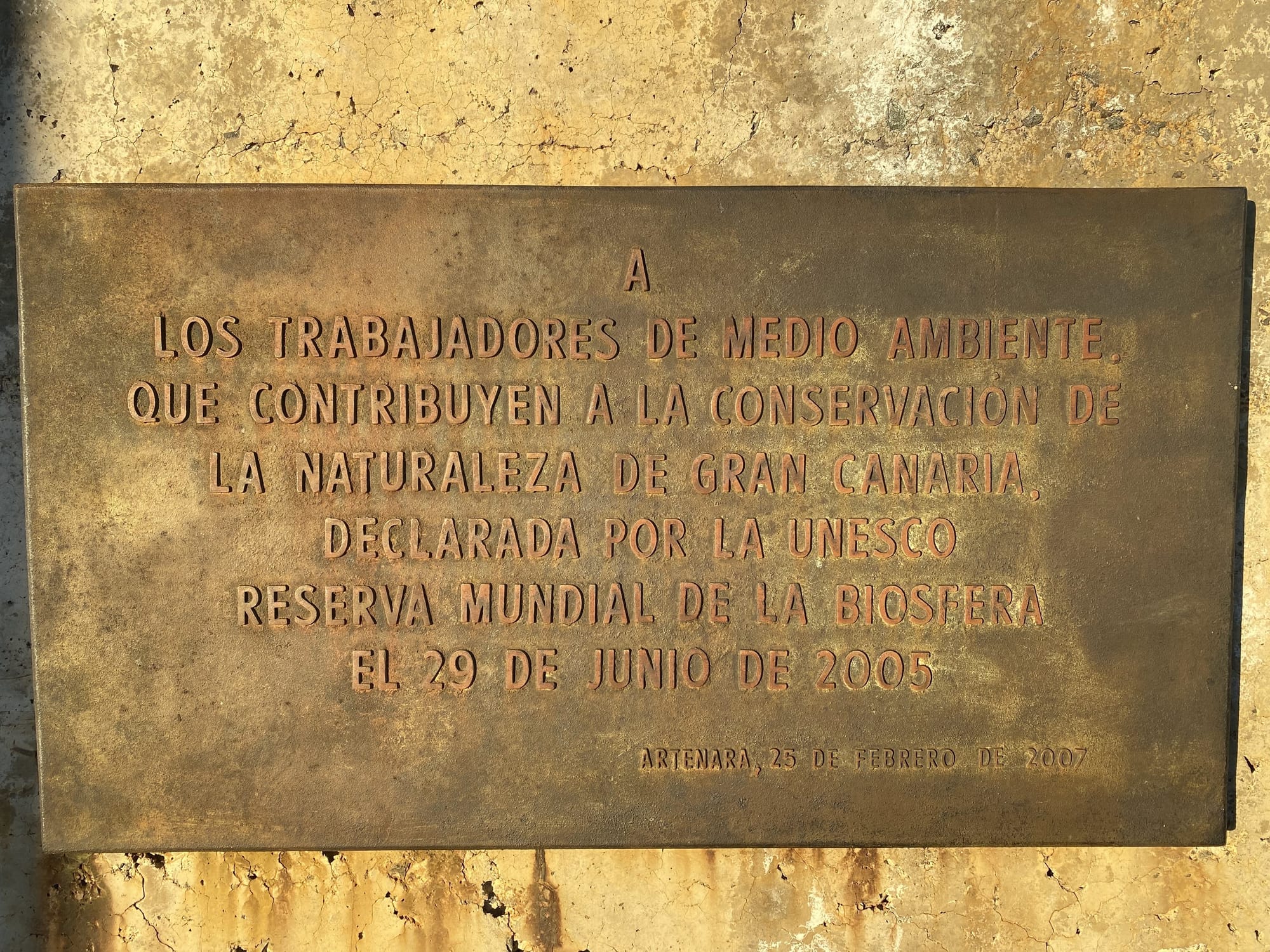

“A los trabajadores del medio ambiente, que contribuyen a la conservación de la naturaleza de Gran Canaria, declarada por la UNESCO Reserva Mundial de la Biosfera el 29 de junio de 2005. Artenara, 25 de febrero de 2007.”

To the environmental workers who contribute to the conservation of Gran Canaria’s nature, declared a World Biosphere Reserve by UNESCO on June 29, 2005. Artenara, February 25, 2007.

*

I’ve been an “environmental worker” of sorts—an environmental organizer—for a decade and a half. Few of those in this line of work expect recognition or honor. In part because it’s not about any one of us. In part because the victories are usually fragile, and the fight always continues.

But also, in large part, because to organize for our rights to air we can breathe, clean water to drink, or a climate that can sustain life often means being on the opposite side of the table from the wealthier, more powerful people who tend to get the official honors and memorials. At least in the U.S.

So to see such a permanent tribute like this, here, so far from home, makes me catch my breath. My eyes well up, in fact. Not because I’m jealous of the recognition. I mean, sure, maybe a little bit. But mostly because of the hopefulness of the idea that a society—a government—could value protecting our environment so highly, and put it on display for all to see.

I stay with it a while, running my fingers over the words.

*

Thirteen months later, I’m at home on my computer when the news breaks: Trump’s EPA has gutted its own ability to fight climate change: It’s rolling back the legal grounding (called the “endangerment finding”) for bedrock climate protections like those on vehicle emissions standards and power plant pollution.

This government has made what it values, and who it works on behalf of, crystal clear—and that’s not the environment, or workers, or definitely not environmental workers. So it’s not a surprising move.

But that doesn’t lessen its danger.

Right now, Spaceship Earth is sounding the alarm, systems wobbling and flashing red. Climate change threatens that beautiful biosphere reserve in the Canary Islands that I visited last year—as it does most corners of the globe.

Last year, the apocalyptic wildfires that leveled parts of Los Angeles while I was in Artenara were intensified by planetary warming.

This year, the Arctic air that’s made winter in Boston feel comfortingly cold—as though “global warming” couldn’t possibly be real—may in fact be a symptom of the system’s breakdown.

Even the increase in human migration, which fascistic regimes around the world scapegoat and use to distract from their own corruption (see ICE in Minnesota), can be linked to the climate crisis.

This was, in fact, foretold decades ago—in internal research by the fossil fuel industry. The same industry that’s fought for years and bought politicians to undermine the just-repealed EPA finding... Call them the “anti-environmental workers,” perhaps.

But! There may be an ironic silver lining to the EPA news.

All around the U.S., right now—and increasingly elsewhere, too—there are many, many groups of people taking climate polluters to court. And not just the usual suspects, the “environmental workers” like me, or people with law degrees (though, of course, their role is crucial).

The Shoalwater Bay Indian Tribe of Washington State.

Local county commissioners from Pennsylvania to Colorado, and city councils from New Jersey to Hawai’i.

Badass youth from Wisconsin to Montana to Alaska.

Farmers from Belgium to Pakistan to South Korea.

The movement to make Big Polluters pay is a big and growing tent worldwide. (Through my work, I’m happy to have played a bit part in supporting it over the last few years.)

But it’s the cases here in the U.S. which directly challenge fossil fuel corporations, in particular, that are a source of surprising hope right now.

Why? Polluters have argued that the EPA already regulates climate-changing emissions at the federal level, so state courts shouldn’t have a say. That’s been core to their defense, and core to their attempts to shut these cases down entirely. But that argument is now undermined.

In other words, Big Oil’s own successful, coordinated efforts to weaken federal climate protections may actually strengthen the cases to hold it accountable.

Those cases aren’t just about accountability. “Environmental workers” like me often take for granted what seems obvious to us: That all of this—whether protecting beautiful landscapes from development, or stopping climate-polluting emissions, or suing Big Oil—is about protecting people’s lives and the planet we rely on.

In Gran Canaria, it’s also about protecting people’s livelihoods that rely on tourism based on nature’s beauty.

Across the U.S., these lawsuits are about preventing more devastating drought, wildfires, flooding. And then making sure that when these disasters do happen, the industries that fueled them, not their victims, are paying for the recovery.

Climate scientists (also environmental workers) have already been warning that we’re reaching tipping points—changes that the climate system can’t recover from. But it’s also possible that we are closer than ever to another tipping point, too: a time when, even in the face of governments as hostile to science and clean energy and kids’ lungs as this one is, the environment—and people—start to win big.

As we walked back down the hill toward the village of Artenara, turning our heads to catch one more glimpse of the sculptures glinting in the fading light, Danny shook his head.

“It’s a shame nothing like that would ever be built in the U.S.,” he said.

He was right, probably. Certainly, it’s hard to imagine right now.

I’ve been unable to find information about the “trabajadores del medio ambiente” who labored to ensure Gran Canaria met the requirements to be a biosphere reserve and secured its designation. I don’t know who they were, whether scientists or elected officials or community organizers or a mix of all. I don’t know what their organizing looked like. I don’t know what sorts of obstacles or resistance, if any, they faced. All I know is the designation process itself is not easy, but they persisted. And I doubt they ever expected a monument.

Perhaps someday, when the fascists and their oil-soaked backers are a short what-not-to-do chapter in our history books, there will be monuments to the people who are fighting these fights right now. Maybe even in the U.S.

Or maybe not.

I’ll settle for us environmental workers—all of us, in the broadest sense, who care about people and the blue-and-green ball we call home—winning these fights.

I’ll settle for a society and governments valuing life—and valuing life’s unique planetary support system.

That may be coming sooner than we think.

That’ll be more than enough.

What else?

- How can we think about focusing on the more distant threat of the climate crisis right now, in the face of abuses like ICE abductions? The always-incisive Emily Atkin’s recent piece is a must-read. (So is her follow-up.)

- Bill McKibben’s latest outlines more reasons why the news from the EPA may become irrelevant.

- My brilliant dearest Cara Smith models, in her op-ed about the closure of a beloved birth center and the failures of the medical system, how to use positional power for advocacy. (Paywalled unless you subscribe to the Philly Inquirer; email me.)

- Shoutout to the best Charlotte Bartter for this video from a neuroscientist on how to “manage that looming sense of existential dread.”

Member discussion