“Thirty people is a lot. Isn’t it?”

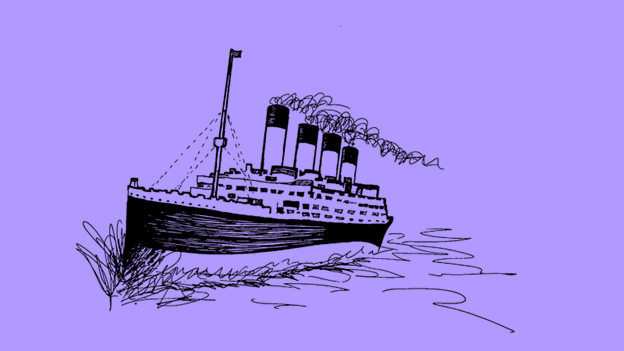

As a hospital ship, the Britannic should never have been a target.

At the start of World War I, the Titanic’s nearly complete younger sister ship was requisitioned by the British Admiralty, outfitted to care for thousands of wounded troops at once, and painted all white with five giant red crosses and a handsome green stripe on each side—visible from miles away. But German mines didn’t discriminate.

On the morning of November 21, 1916, the Britannic steamed full speed ahead into the Kea Channel in the Aegean Sea. The ship was en route to Lemnos to pick up injured soldiers, with more than a thousand doctors, nurses, and crew on board. At 8:12 am, under morning sunshine, an explosion shuddered through the hull: the Britannic had struck a mine planted by a German U-Boat a month before. The captain, attempting to beach the ship on the island of Kea, ordered the lifeboats readied but not launched. Nevertheless, one officer sent two lifeboats off into the water. Both were sucked into the still-churning propellers.

Less than an hour after striking the mine, the Britannic sank to the bottom of the sparkling Mediterranean. But only 30 people lost their lives in the disaster—all people who had been aboard those two rogue lifeboats.

*

“What do you mean, ‘only’ 30 people?”

Mom turned to me, spatula raised. She was stir frying vegetables for dinner, the steam from the pan mingling with her black curls. One eyebrow was arched, and her lips pressed into a serious line. Unusually serious. Usually, we were silly—her, cooking dinner; me, age 10 or so, prancing around her in the kitchen spouting Titanic facts. But right now, there was an unusual sharpness in her voice.

“Well,” I said, a little sheepish. “Compared to the number of people who died on the Titanic. That was, like, 1,500 people. This was only 30.”

She shook her head. “Not only. That’s still a lot of people to die.” Her voice softened. “Think about how sad it is when one person dies. Thirty people is a lot. Isn’t it?” She studied my face for a moment, shook her head, and turned back to the stove.

I’ve been struggling to sleep lately.

Actually, that doesn’t quite capture it.

Many nights, I’ve gotten in bed, clicked off the bedside lamp, and lain awake, fighting to breathe deep and slow my heart rate as the day’s news infiltrates my mind. I’ve wiggled my toes, feeling alternately itchy, overheated, cold, and on the verge of tears. Or I’ve woken up early, long before the blue light of winter starts to bleed around the edges of the bedroom blinds, and kept my eyelids screwed shut, willing my mind—fruitlessly—to melt back into sleep. A dull sadness radiates through my body, punctuated by twitches of anxiety.

People are dying, I think.

Renée Nicole Good, shot, Minneapolis, January.

Mukhammad Aziz Umurzokov and Ella Cook, shot, Providence, December.

15 people celebrating Chanukah, shot, Bondi Beach, December.

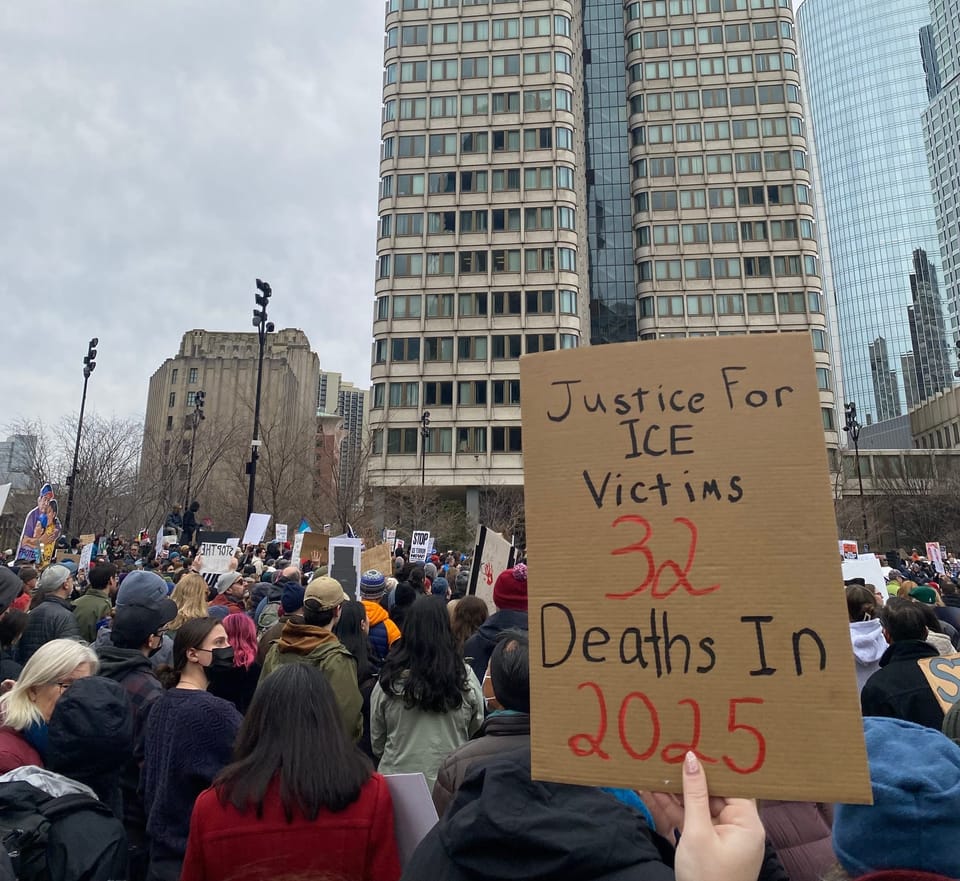

32 people, various causes in ICE detention, 2025.*

More than 80 people, shot or bombed, Caracas, January.

1,200 people, shot and more, Israel, October 7, 2023.

More than 70,000 people, shot and more, Gaza, since then.

There are many more. But these are the people most frequently on my mind these days.

The loss of human life is one thing. That’s where the sadness comes from.

But the loss of humanity is what’s really keeping me up at night.

*

Here’s what I mean.

Renée Good was a white, queer activist in her 30s, like me and many of my friends. She was doing something that, until 2025, we believed was a relatively safe activity for someone like us: documenting the activities of government agents. Simply bearing witness to abuse. She should never have been a target.

From the U.S. government’s official accounts, however, and from the right-wing news outlets and social media platforms I follow, however, you get a very different understanding. The readily debunked pieces of propaganda make various claims about who she was and what happened in the last few minutes of her life, but they aim toward the same thing: to convince us that she deserved it. She deserved to die.

And it’s not just her.

Every single one of the deaths I listed above has been justified by someone on TV or the Internet. Someone has publicly said some version of they deserved it. And suddenly the conversation has shifted: from the horror of death to who deserves to die. From tragedy to us vs. them.

This isn’t new. Black folks know it. Queer folks know it. Jews know it; Palestinians know it. Make someone or a group the other, and blame them for their fate. What feels unsettingly new to me is how fast and blatant it is, with no pretense of collective mourning for even a few days.

They deserved it has become an immediate, mainstream response to death.

And it creates social permission for more death.

Who benefits from this? Who benefits from this zero-sum thinking, from convincing us that someone, or some group of people, deserves to die—that they were so dangerous that the rest of our safety depends on their death? No one—except for people in power, harnessing fear to justify violence, to deflect from abuse, to maintain their power.

When they’re successful, it erodes all of our humanity.

And it works. Even, I hate to admit, on me.

How many times have I thought they deserved it? It’s easy to think it at once, seeing a headline; to feel the momentary full-body flush of anger. The whole point is how easy it is.

Yet wishing death upon someone is a serious thing. Who truly believes they could kill? Can the people posting, from behind blue-lit screens, that Renée Good deserved it really imagine themselves, holding a gun, face-to-face with another human being sitting in the driver’s seat of her car, and think, yes, pulling this trigger is the right thing to do?

All that mattered in that instant was that one person thought so. In that instant, he couldn’t register her humanness. So he pulled the trigger.

What frightens me even more—what robs me of sleep so many nights—is how many other people have been convinced to believe he was right… and how that creates permission for it to happen again. And again. And again.

*

Jewish tradition teaches that to save a life is to save an entire universe. It’s rooted in the Mishnah and the concept of pikuach nefesh—that the obligation to save a single soul overrides nearly every other rule.

The Qur’an has its own version of this teaching: “Whoever kills a soul... it is as if he had slain mankind entirely. And whoever saves one—it is as if he had saved mankind entirely” (Surah Al-Ma’idah, 5:32).

The headlines and social media posts and articles reduce every life to a set of nouns and adjectives, no matter the author. Renée Good was either a domestic terrorist or a queer activist mom hero.

For her wife, though, and for her son, she was a universe.

*

When I’m struggling to hold all of it, sometimes, I think about one person I love. Someone really dear to me. I think, what if they were suddenly… gone? I think about the things we’ve done or do together, or a recent conversation, and I feel the waves of sadness rise from my belly to my throat and start to pull me under. And then I remind myself that they’re not gone—but that somewhere, someone is feeling this way, only worse. About Renée Good. About Awdah Al-Hathaleen. About Matilda. Because their beloved is actually gone, very publicly gone, and there are people all over the internet saying they deserved it. It’s hard to imagine dying; it’s easier to put myself in the shoes of the people who loved them, who have to go on living through their grief.

We human beings aren’t wired to comprehend death beyond the individual level. Even a number like 30 becomes abstract.

So sitting with a shadow of their grief tunes me into my empathy. It brings me closer to feeling an individual death as the loss of a universe.

Or perhaps what I mean to say is, it connects me to my, their, all of our humanity.

*

I went to an ICE Out rally in Boston last weekend. Thousands of people showed up. Under a somber gray sky and the beating drone of a helicopter’s blades, we grieved—not just for Renée Good, but for all 32 people who died in ICE custody last year.

Thirty people is a lot. Isn’t it?

I grieved, too, for everyone who’s died in the violence of the last few years. I stood there and felt my eyes well up—actual tears, for the first time in ages—for all of those people. And I felt connected with the human beings around me, feeling the same things, together.

I refuse to be convinced that any of these people deserved to die.

*

Here’s my touchstone: I have to believe that “loss of empathy” or “loss of humanity” isn't really the right phrase for it. Our humanity is a muscle that is atrophying, that needs to be exercised—and can be. It’s a thread that binds us as human beings that is fraying, but not broken. Or perhaps most accurately, it’s a lifeline that’s being tugged from our hands by those who benefit from making us fear one another—but the rope is still ours to hold fast to.

Even at age 10, I could tell that the conversation with my mom about the Britannic had unsettled her. I recognized that her child’s apparently blasé attitude toward mass casualty had disturbed her. I don’t remember what else she said, or if she said anything else. The question stuck with me. The question was enough. Thirty people is a lot. Isn’t it?

I learned a lesson from my mama that day. Every life matters. Every life is a universe.

I’ll keep working toward a world where we all act as though that’s true.

Love,

Ari

*The Guardian kept a running article with brief profiles of each of the 32 people who died in ICE custody in 2025. It is hard to read, but worth it: it made me feel deeply sad, which is to say, human.

P.S. Happy Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Day. “We cannot long survive spiritually separated in a world that is geographically together.” —MLK, “On Being a Good Neighbor,” Strength to Love.

Member discussion